CatColab v0.4: Robin

Since our last blog post about CatColab, we’ve had two releases, meaning we’re now at v0.4: Robin. This brings a few major new features, including compositional notebooks and novel analyses for Petri nets.

Continuing our theme of naming CatColab releases after increasingly larger (yet still very tiny) birds, we’ve recently released v0.4: Robin. There are quite a few new features to showcase: some big and some small, some visible and some hidden. For those interested in implementation details, you can view the non-curated list of release notes on GitHub. Note that this blog post also talks about features from the previous release (v0.3) since we missed doing a blog post for that one — we were just over-excited adding features and polishing bits.

New features and updates

Petri nets

Petri nets are important and widely used graphical formalism for modeling processes that can consume and emit typed tokens, from concurrent computer systems to biochemical reaction networks. To quote from catcolab.org/help/logics/petri-net:

Petri nets were invented to express discrete-event dynamical systems with concurrency, or networks of resources and processes, describing how various states (called places) relate to one another in terms of transitions. Each transition has incoming and outgoing arrows (called arcs) connected to places, which describe the input and output places of the transition (respectively).

One way of understanding Petri nets is through their token semantics. We place a number of “tokens” in each place and then check all the transitions to see if all their input places have a token: if so, then we can “fire” the transition, moving the tokens from the input places to the output places; if not, then nothing happens. In many classical references the token semantics are built directly in to the definition of Petri nets (often called a marking or tokening), but an unmarked Petri net is already itself a useful formal gadget, analogous to how can be useful to consider an ordinary differential equation without giving its initial conditions.

Quite a few category theorists have written about Petri nets; some of John Baez’s blog posts give a pretty comprehensive overview. There is a plethora of literature concerning Petri nets in all their various flavours and guises, and it’s a non-trivial task to try to figure out where different sources actually agree or disagree. The version that we currently have implemented in CatColab is that of free presentations of symmetric monoidal categories, though you don’t need to actually care about this in order to be able to use them.

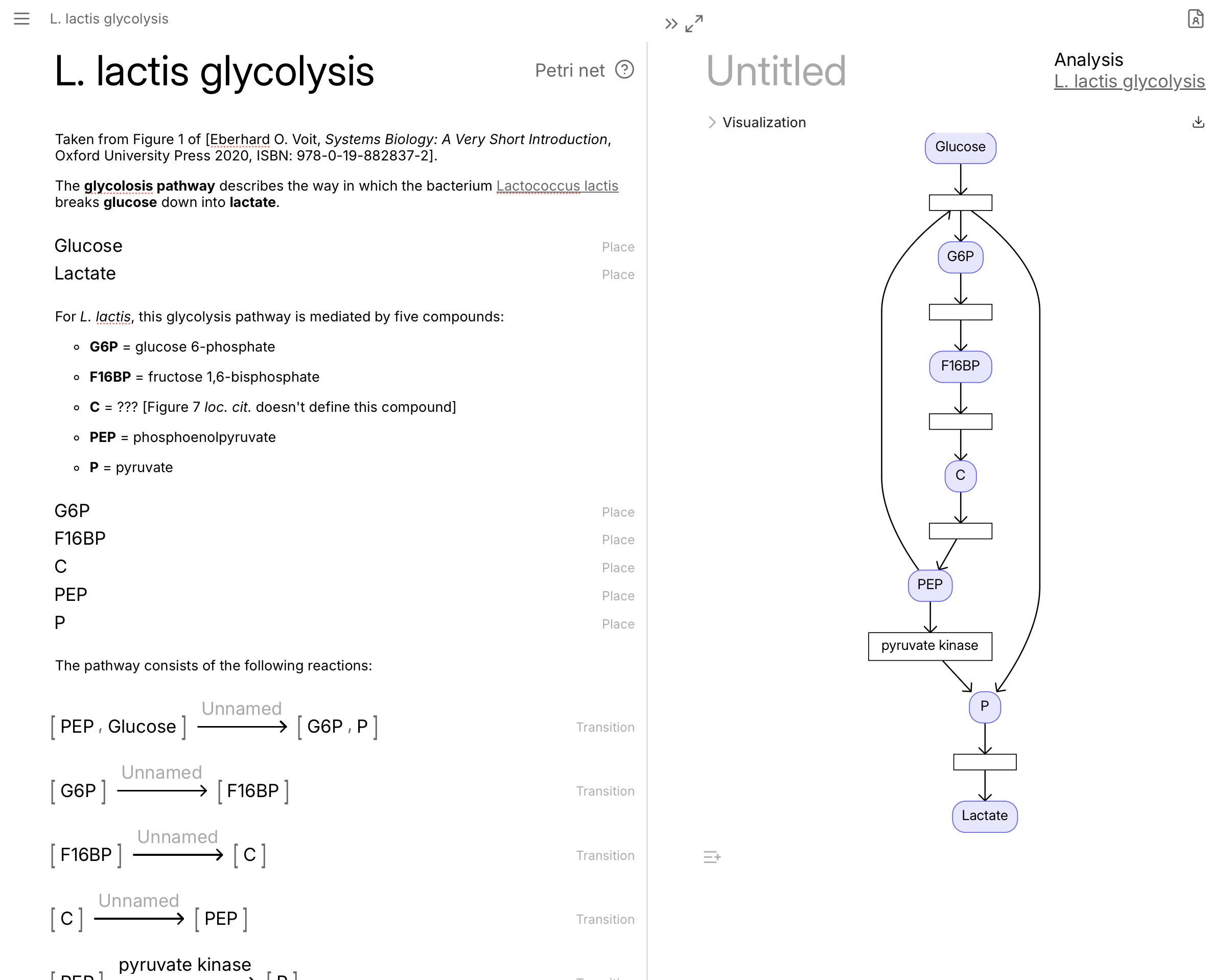

For an example, below is a screenshot (and a link to the CatColab notebook) of a Petri net describing the pathway by which a certain bacteria breaks glucose down into lactate, taken from an introductory book on systems biology.

With this new logic there come also three new analyses, thanks to some grand efforts:

- ODE simulation based on population-level mass-action dynamics

- Stochastic simulation based on individual-level mass-action dynamics (thanks to Matt Cuffaro!)

- Model checking of sub-reachability from initial state (thanks to Kris Brown!)

For full details, you can read the Petri nets documentation, but in brief the first analysis checks whether or not certain tokening states can be reached from a given initial state, and the second and third analysis simulate so-called mass-action dynamics, which envisions Petri nets as describing concentrations of quantities and the reactions that can take place between them. The third analysis, in particular, in particularly exciting, since it is the first instance of a stochastic analysis inside CatColab.

Compositional models (of discrete theories)

Something that we at Topos have been talking about for a while as a fundamental capability of a categorical approach to modelling (far from just in conversations about CatColab) is the ability to compose models. If somebody has made a model describing some system, which I then want to view as a component of my other system, I would like to able to instantiate it and use it within my model. This is now possible for certain theories1 in CatColab!

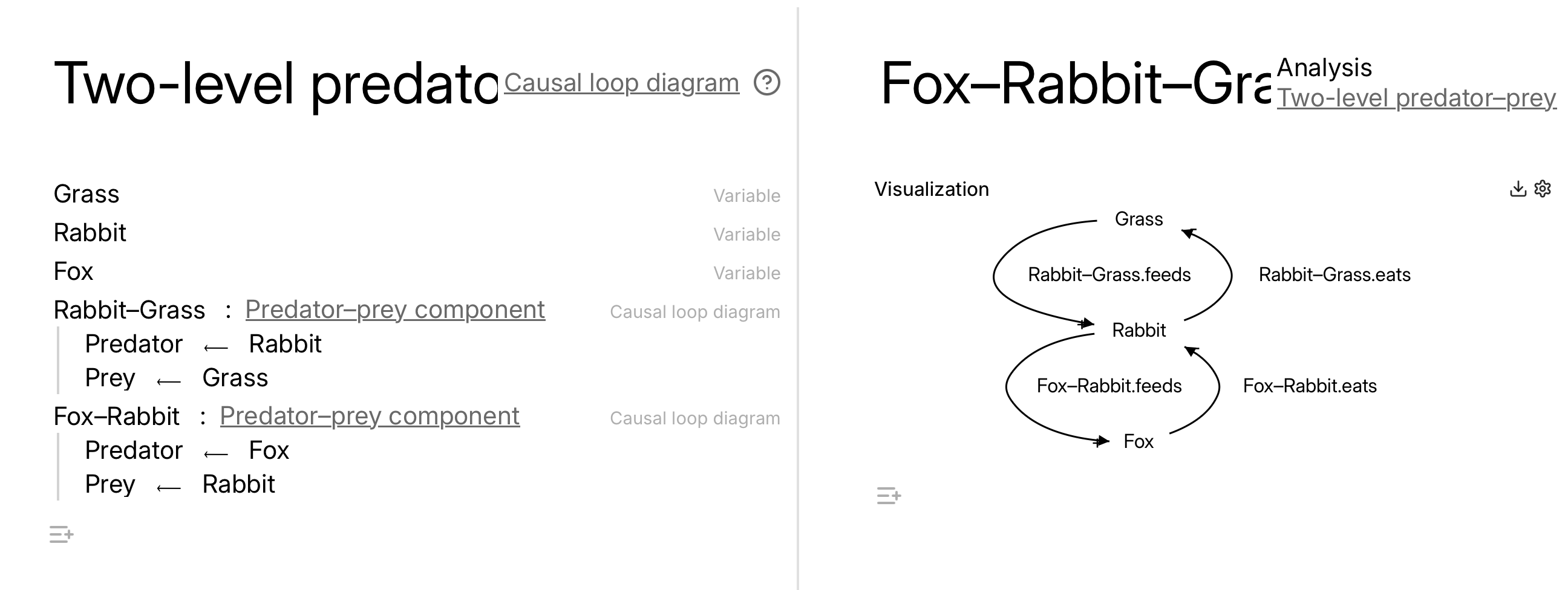

As a small example, we can create a causal loop diagram with two variables, one positive link, and one negative link: \begin{aligned} \texttt{Prey} &\xrightarrow{\texttt{feeds}}^+ \texttt{Predator} \\\texttt{Predator} &\xrightarrow{\texttt{eats}}^- \texttt{Prey} \end{aligned} This is a “toy model” (or, more properly, a motif) for a general predator–prey scenario, where an increase in the population of prey can cause an increase in the population of predators (more food for them to eat), but such an increase can cause a decrease in the population of prey (more predators to eat them).

Now say we want to actually build a two-level model, where we have foxes, rabbits, and grass. Here the foxes and rabbits form a predator–prey relationship, as do the rabbits and grass, so we would like our model to reflect this symmetry. In CatColab, we have a new cell type: Instantiate. This lets us import an existing model and bind its exposed variables to those in our larger model, as we show in the screenshot below.

Even this relatively simple example illustrates the idea that many complex models are built out of a library of such “standard components”.

Those of you familiar with object-oriented programming, or structs in languages like C or Rust, might find the notation rather suggestive, where we write Rabbit–Grass.feeds to refer to the feeds arrow in the Rabbit–Grass instantiation. This blog post isn’t the place to delve properly into this analogy, but we will at least mention some of the mathematics here.

Under the hood, the compositional models feature of CatColab is based on recent work by Owen Lynch on DoubleTT (where the TT stands for type theory), which is what allows for our implementation of instantiation. The test.dbltt.snapshot example showcases some of the functionality of DoubleTT. For example, we can define a type called Graph as

type Graph := [

V : Entity,

E : Entity,

src : (Id Entity)[E, V],

tgt : (Id Entity)[E, V]

]and we are then able to define a type called Graph2 as

type Graph2 := [

V : Entity,

g1 : Graph & [ .V := V],

g2 : Graph & [ .V := V]

]which results in the type that we get from taking two copies of Graph and “gluing them along their vertex object”, i.e. the type of a graph with two colours of edges.

Documents and landing page

Since joining our team not so long ago, Kaspar Bumke has been hard at work in overhauling the user experience. One of my personal biggest complaints was that every time I opened up CatColab it created a new blank document, which was compounded by the fact that there was no ability to delete documents. Both of these usability problems, amongst others, have now been solved!

The landing page for CatColab is now a nice splash page with all the useful links, including one to “My documents”, and when viewing your documents you can soft delete them (i.e. move them to a recycling bin and recover them at a future date). This is just the start of a much larger project focussed on improving UI/UX around documents.

Rich text and UI refresh

As in the screenshot of the L. lactis glycolysis Petri net model above, analyses open in a side-pane as opposed to a whole new page, making it much easier to understand how analyses change as you modify the underlying model. With v0.4, this panel-based navigation is now present throughout all of CatColab! Not only that, but analysis documents are now first-class, in the sense that they can be named, permissioned, and shared just like any model document can.

Another thing from the Petri net screenshot that’s a bit more subtle, but just as useful, is the capability to have rich-text cells within a model. This means that we can support not just formatting like bold and italic, but also links and mathematics (rendered with KaTeX). Getting this to work has been remarkably subtle, and it’s really thanks to Jason Moggridge for fixing the myriad of little frustrating bugs that blocked us from releasing this for so long. The basic issue is that our rich-text support is based on automerge-prosemirror, which uses features of the Automerge document format going beyond standard JSON. So we had to re-architect our backend to make Automerge docs, rather JSON objects, the source of truth. This was supported by our friends over at Ink & Switch, who are the lovely people behind Automerge itself.

What next?

CatColab is now at the stage where we can start having serious conversations with experts from different disciplines and try to understand what they want and need from software. We have some exciting conversations planned already (for example, the AIM workshop on Formal scientific modeling: a case study in global health), but we’re entering into 2026 with more ideas and possibilities than we will ever possibly have time to work on to completeness.

But this is good news! Not only is it exciting for us to have a wide choice of possible projects, but it can also be exciting for you to be involved in helping steer the direction. If you’re interested in the software, the underlying mathematics, the ways in which it could fit into existing (or possible) real-world contexts, or have questions or desiderata, then we’d love to hear from you and chat about it all. The easiest way to join in the conversation is in our Zulip:

Footnotes

At the moment, only discrete theories support this compositionality, but we are working on implementing this for more complex theories for a future release.↩︎